By Vince Cooper

It’s very rare for a player to be chosen as ‘the best ever’ by two different teams. Charlie Hurley was that man.

Big in both size and character, Hurley developed his career in London’s Docklands, then saw it flourish in the North East, building such a reputation that he was voted Sunderland’s ‘Player of the Century’ whilst also earning the title as Millwall’s ‘Best-ever Player’ during his time in the East End.

Hurley was born in Cork, Ireland in October 1936 but his family crossed the Irish Sea when he was just seven months old, Dad taking a job at Fords in Dagenham and the family settling in Rainham, Essex with the number of children eventually rising to 11 (of whom seven survived).

After living through the Blitz, Hurley started playing football at school, captaining his Sutton School team despite initially being forced to play in plimsolls because the family couldn’t afford boots. He impressed enough to be chosen for London Schools and was about to be invited for England trials when an eagle-eyed selector decided to check out his history, the birthplace ruling him out of further progress.

When he was 15 one of the teachers at his school decided he deserved a crack at the big time and arranged for a trial with Arsenal. Playing against players much older than him he still managed to impress enough for Gunners boss Tom Whittaker to tell him he’d send for him in a couple of years.

When he left school Hurley followed his father, brother and brother-in-law in getting a job at Fords, working as an apprentice toolmaker. As a 16-year-old he was on West Ham’s books and they offered him a full-time position on the groundstaff. But the money Charlie was earning at Fords was £1-a-week more – a big difference in the 1950s – so he turned down the chance to become what he later described as ‘a glorified boot cleaner’. At the same time he denied the footballing world the possibility to see him line up alongside Bobby Moore.

Soon after, Millwall spotted him playing for Rainham Town Youth Club against Walthamstow and snapped him up, signing him as a professional and paying £7-a-week, rising to £10 if he made it to the first team. He chose the East End club over a number of other possibilities, later saying; “It just appealed to me. I liked the ground and the crowd.”

An early Millwall team group

Within a year Hurley was earning that extra £3, having made his debut in a 2-2 draw at Torquay with the Sunday Dispatch describing him as ‘very impressive’ and he quickly became a regular in the line-up. He would later describe his debut, which his parents couldn’t afford to travel to as; “One of the best days of my life. I was a professional footballer. Marvellous, absolutely marvellous”.

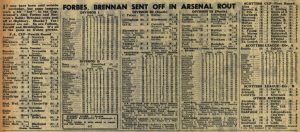

,Charlie‘s debut

Despite the big, strong build of a traditional centre-half there was more to Hurley’s game. “This is a man who strokes the ball as if he loves rather than hates it”, a Daily Express reporter would say later in his career. “he never needs to hurry.”

Charlie in the Army

Charlie’s 1953-54 season was interrupted towards the end by his National Service but he still managed to make 14 appearances, and a big impression.

Limbering up at The Den

Four years with The Lions would bring over a century of starts and an undoubted highlight was his appearance for the capital’s representative side against Frankfurt in the Inter Cities Fairs Cup.

Played at Wembley in the stadium’s first-ever match under floodlights, the home team, including Chelsea’s Roy Bentley, Bobby Robson and Bedford Jezzard of Fulham and Spurs legend Danny Blanchflower, fell two behind in the first half with the first German goal coming from a penalty conceded by Hurley.

London roared back in the second period with two goals from Jezzard and one from Robson earning them a 3-2 win in driving rain and Hurley, along with Chelsea full-backs Peter Sillett and Stan Willemse, holding the Germans at bay, the Daily Mail headline reading; ‘Hurley holds Germans’.

Having originally been picked for Ireland in 1955, Hurley was forced to miss his debut due to a serious cruciate injury sustained whilst playing for the Army Catering Corps and he spent over a year on the sidelines. Having spent six weeks at a rehabilitation centre he recovered well enough that towards the end of his time in East London Hurley was called up for a second time to make his debut for his country against England in a World Cup qualifier and given the daunting task of marking Tommy Taylor.

The Manchester United man had recently scored a hat-trick against the Irish but Hurley did a fine job of quelling the threat. Alf Ringstead gave the Irish a 3rd-minute lead and England only snatched a draw thanks to a late John Atyeo goal.

Writing in the Daily Mirror, Archie Ledbrooke said; “It was the Irish who produced a new great world class footballer in centre half Charlie Hurley.

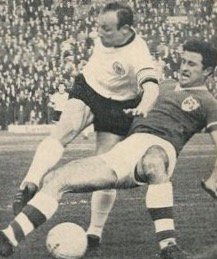

International duty. Charlie tackles West Germany’s Uwe Seeler

“Half the clubs in the First Division will soon be knocking on Millwall’s door offering £25,000 for him”, concluded Ledbrooke.

Having made a full recovery from the injury which had seen him spend a total of fifteen months on the sidelines, Charlie went into training one Monday morning in September 1957 and was informed that Sunderland manager Alan Brown was there to see him.

He later admitted that, at that time he didn’t even know where Sunderland was and he had no intention of joining the club. But Brown met with the player, his parents and the rest of the Hurley family at their home in Rainham.

The Sunderland boss was determined to get his man and, having arrived at 10 in the morning finally managed to convince him at 8:30 that evening and the Black Cats got their man in with a cheque reportedly for £18,000 changing hands and with Hurley receiving a £10 signing-on fee.

”When I did sign”, said Hurley the next day, “Mr Brown almost jumped through the roof. I’ve never seen a man so excited”.

When he moved to Roker Park the club were reeling from the ‘Mr Smith’ illegal payments inquiry which had seen them fined, a number of directors suspended and Brown replacing Bill Murray who had been in charge for 18 years.

Sunderland were struggling on the pitch too and fourth from bottom when Hurley was brought in for his debut at Blackpool. Things got worse. Late in the match at Bloomfield Road an attempted Hurley clearance hit Ernie Taylor in the face and rebounded into the goal for Blackpool’s seventh with the visitors failing to score in reply. “It was a shocker” the Irishman, whose performance was described as ‘too dainty’ said after the match.

The next week Sunderland travelled to Burnley to meet Brown’s former club. Things got better but only marginally as they crashed to a 6-0 defeat. Two games for the centre-half, 13 goals conceded.

The whole season was a real baptism of fire at the top level for Hurley. A team in which Brown regularly chose inexperienced youngsters over veterans was relegated on goal average having finished level on points with Portsmouth and local rivals Newcastle in a three-way tie for 20th place. The final day of the season brought a 2-0 win over Portsmouth but it wasn’t enough to stave off the drop, ending a then-record top-flight run of 68 years.

For their 2nd Division experience, youngsters Len Ashurst, Jimmy McNab and Cecil Irwin joined Hurley in a youthful line-up with an average age of 21. Unsurprisingly inconsistency was the order of the day with the youngsters improving as the season went on and climbing to finish 15th.

A second season of mediocrity followed with a 16th-place finish and Hurley still seemingly learning his trade. “Once we started sliding it was difficult to stop” said the now-skipper but Brown’s insistence on giving young players experience clearly made progress more difficult.

Captain Charlie,

The 1960-61 season was clearly Hurley’s best so far in red and white stripes as the team climbed to 6th in the second tier as well as going on a cup run which would see them eliminate Arsenal, Liverpool and Norwich (where he got the only goal in what some claim was the finest of many great performances for the club) before falling to eventual winners Spurs. It was also in that season that the Irishman started going up to join the attack for corners and free-kicks, now a regular part of the game but then unheard of. He had scored in the 1-1 draw with Sheffield United and soon earned a reputation as a new addition to the attack at set-pieces, either scoring himself or setting up numerous opportunities for others. Thus began the chant of ‘Charlie, Charlie, Charlie’ whenever the team won a corner as the fans urged him up the pitch.

In the summer of 1961 when the club splashed out £80,000 on George Herd and Brian Clough they suddenly became promotion contenders. In fact there would be a pair of heartbreaking near misses.

A win on the final day of the 1961-62 season would have given them promotion but the Black Cats 1-1 draw with Swansea and missed out. The following year it was goal average again that saw them fail to climb, this time with Chelsea taking advantage. The loss, which would prove permanent of Brian Clough, who had bagged an astonishing 28 goals in the first half of the season, to injury on Boxing Day 1962 was the crucial factor.

Chaired by teammates after promotion

Despite the absence of Clough, the 1963-64 season proved third time lucky for Hurley’s team as they finished runners-up to Leeds United and returned to the top flight. Again it was a final day nailbiter but this time Hurley’s team came through despite going a goal behind to Charlton. They turned things around and won 2-1, finishing with a lap of honour, which Charlie says was; “Probably the greatest moment of my entire career.”

Scoring against Everton

A memorable season was enhanced by another fine cup run including a 5th Round humbling of champions Everton (Hurley netting in a 3-1 win) and an epic quarter-final with star-studded Manchester United.

With Manchester United captain Denis Law

Sunderland were 3-1 up at Old Trafford – despite a Hurley own-goal. But United hit back with strikes from Bobby Charlton and a last-minute George Best equaliser sending the match to a replay.

When the teams met again Roker Park was packed to the rafters. The gates came down at the Roker end of the ground allowing thousands to flood in. Some estimates put the attendance at 80,000 with 40,000 more outside.

Again Sunderland led; again United equalised in the last minute, this time through Charlton, so the teams would have to meet for a third time.

Leeds Road was the setting for part three and Nick Sharkey gave Hurley’s men the lead just after the interval. But United scored three quick goals in reply and eventually went through with a 5-1 win.

But the main aim – promotion – had been achieved, and this time Hurley was ready for the 1st Division. Journalist Norman Fox said of him at the time: “The jaunty confidence of Charlie Hurley is no more than the attitude of a man sure of his task and aware of his value.”

But before the new campaign started the club was rattled when manager Alan Brown quit after not being offered a pay rise. Hurley admitted that the departure of the manager rocked the club. “The players had tremendous confidence in him.” He would later say.

Arthur Wright and Jack Jones took temporary control and then George Hardwick came in, leading the side to a relatively comfortable first season back at the top.

Charlie gets to grips with fellow Irishman Terry Conroy of Stoke City

Next Ian McColl took charge and it was clear from very early on that he and Hurley didn’t see eye-to-eye. The captain was left out of the team in favour of George Kinnell, a cousin of Jim Baxter, the club’s new star man.

McCall stayed with the club for two-and-a-half seasons mostly highlighted by struggles at the foot of the table and Hurley was clearly a relieved man when he left in early 1968.

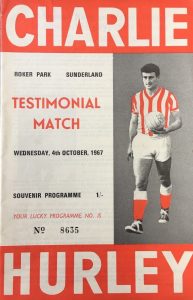

The testimonial programme

Hurley was awarded a testimonial by the club in 1967 and he put together Charlie Hurley XI to face an International XI that included Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters in a match that finished 5-5.

Press tributes in the programme for the match included Bob Wood of the Sunday Telegraph saying; “He belongs to the immortals” and Jackie Milburn of the News of the World – himself a hero of North East football who said; “Any player who earns the nickname ‘King’ from North East sports followers any player has to consistently show skill, class and complete dominance. Charlie Hurley has achieved this with regal distinction.”

The return of Alan Brown to the manager’s seat saw another season succesfully fighting to avoid the drop and the end of it also saw the end of Hurley’s time at the club although there was still time to nurture future England star Colin Todd through the early stages of his career.

At the same time as he was leaving Roker Park Hurley also saw his international career draw to a close. He won a total of 40 caps for Ireland, scoring twice and standing out in a team that often lacked its other star men due to club commitments.

A muddy day at Bolton

Given a free transfer he moved on to Bolton although his time at Burnden Park was hampered as he needed to take time off when his daughter was ill and found it tough to get back into the side. As his career was drawing to a close he was offered the manager’s role at the club but turned it down as he wanted to take his family back to the South of England.

Charlie with wife Joan and daughter Tracey

After three years in Lancashire the time had come to hang up his boots and Hurley moved into management, taking charge at Reading where his most successful spell came after signing Robin Friday from non-league Hayes with the Royals winning promotion to the 3rd Division. But Friday was then sold to Cardiff and the club were relegated after which the manager resigned.

There is no doubt that, despite spending most of his career playing for a team struggling in the 1st Division or fighting for promotion from the 2nd, Charlie Hurley was right up there with the best centre-halves of the 1960s.

Had he been part of a more successful Sunderland team, had he moved to another top-flight club, had the ‘residency rule’ been in place for internationals enabling him to represent England, the huge regard Millwall and Sunderland fans (‘who’s the finest centre half the world has ever seen’ could often be heard ringing around Roker) as well as followers of the Ireland team, have for the big centre-half might well be even more widespread.