THE JOE MERCER STORY

By Vince Cooper

FOR many, the mark of a true football great is one who reached the top both on and off the pitch. To have made it to the pinnacle both as a player and a manager is evidence of skill, of the ability to have learned from your playing days about tactics and motivation, and of the ability to communicate, educate and pass those lessons on to the players now in your charge.

These greats are few and far between so there really must have been something special about Cambridge Road School in Ellesmere Port which produced not one but two of these footballing icons at the same time.

Joe Mercer and Stan Cullis both made their way to the very top as players, representing England at the highest level although they had careers on the pitch that might have been even greater but for World War Two. Then after hanging up their boots, both turned their hand to management and replicated the achievements produced on the pitch.

Mercer and Cullis both also displayed a great level of pride and loyalty although sadly this was not always returned by the clubs they served so well.

Although their careers were intertwined, a combined article wouldn’t do them justice so I’ve decided to write separately about each. The Stan Cullis Story is elsewhere on this site, here is Joe Mercer’s.

Joe Sr

Joe Mercer Jr was the eldest son of Joe Mercer who himself was a professional footballer. Mercer Sr was a tough, no-nonsense centre-half and started out with Ellesmere Port Town before joining Nottingham Forest in 1910. He almost signed for Everton but when Toffees manager Walter Cuff went to watch him play he reported back; “He’s a good player alright, but he’d get us thrown out of the league!”

Four months after the start of World War One and a day after the 17th Middlesex, the famed ‘Footballers Battalion’ was formed Mercer travelled down to London with teammates Tom Gibson and Harold Iremonger to enlist. In 1915 the Battalion was posted to the Western front where Mercer was promoted to Sergeant. After suffering wounds to his head, leg and shoulder and being gassed, he was captured at Oppy in 1917 and spent the final year of the hostilities in three different Prisoner-of-War camps before finally being released in January 1919.

When he came home Mercer brought back a football for his 4-year-old son, to whom he was a virtual stranger. He tried to resume his playing career, spending some time with Tranmere Rovers but found it impossible to perform at his former level due to the injuries suffered. He retired, going back to bricklaying, his original trade. He sadly passed away, aged just 37, in 1927, succumbing to health problems brought about by the gassing he had suffered in the trenches.

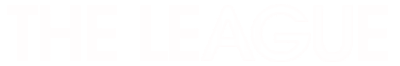

Joe Mercer Jr, just 12 when his dad died, had put that football to good use and was already starting to show signs that he would follow in his footballing footsteps. In 1929, aged 15 he was chosen, alongside schoolmate Cullis, to represent Ellesmere Port Boys against Chester. A left-half, Mercer was strong in the tackle and also a great reader of the game and even at this early stage it was clear he had the ability to go a long way.

Mercer admitted later that early experiences on the streets of Ellesmere Port had prepared him well. “The back alleys held some valuable lessons”, he recalled. “For instance, playing with a small ball. If you could control a small ball with certainty, you found later that bringing down a normal ball came more easily. It was wonderful training for the eye”.

His dad’s passing left Joe as the family’s principal breadwinner and on leaving school he took a job in an oil refinery, giving him less time to play the game he loved although he still found time to turn out for Ellesmere Port Town where he received his first football payment – 6d and a bag of vegetables.

But the skills hadn’t gone unnoticed and Everton, after watching him play for Ellesmere Port Town and for Cheshire schoolboys where he lined up alongside Cullis and another future international, Frank Soo, swooped in and offered him a deal. Joe’s mum insisted that he spend some time in the reserves before making a final decision and, a six-match spell completed, he joined The Toffees, signing professional forms for £5 a week.

At the age of 18, he made his debut for the Goodison Park club against Leeds United at inside-right.

At the time he joined the club, Everton had a formidable line-up, featuring the likes of Dixie Dean, Warney Cresswell, T. G. Jones, Cliff Britton and Ted Sagar among others. With such a strong starting XI it is little surprise that it took Mercer a while to break into the first team but he bided his time, learned valuable lessons from his more experienced teammates and eventually his all-action style won him a place in the line-up.

It was in the 1935-36 season that Mercer finally became a regular having moved back to wing-half where he formed a strong partnership with the aforementioned Britton. From then until the outbreak of war, Mercer made the left-half position his own and in 1938 he earned the first of a pitifully small total of five England caps (although he also made 26 wartime appearances, many as captain) when playing in the 7-0 win over Northern Ireland at Old Trafford.

Everton 1938

The 1938-39 season was a fine one for Mercer, and for his club. Not only was he now establishing himself in the England side, his team, with him at the heart of things and Tommy Lawton banging in a division-leading 35 goals, won their fifth 1st Division title.

Lawton later said of his teammate; “Joe Mercer was a tremendous tackler, timing his interventions perfectly, and he loved nothing more than to bring the ball up and take part in an attack with his forwards.

“He had deceptive speed, but then Joe was a deceptive player, probably due to those bandy legs of his”.

What could easily have become a team that dominated football was ruined however when the League was suspended with the outbreak of hostilities.

On the outbreak of war, Mercer was among the many top players invited to become a Physical Training Instructor at Aldershot. There, he played alongside many of the leading players of the time for Aldershot, including forming an imposing half-back line (as pictured above) with schoolboy pal Cullis and Everton teammate Britton.

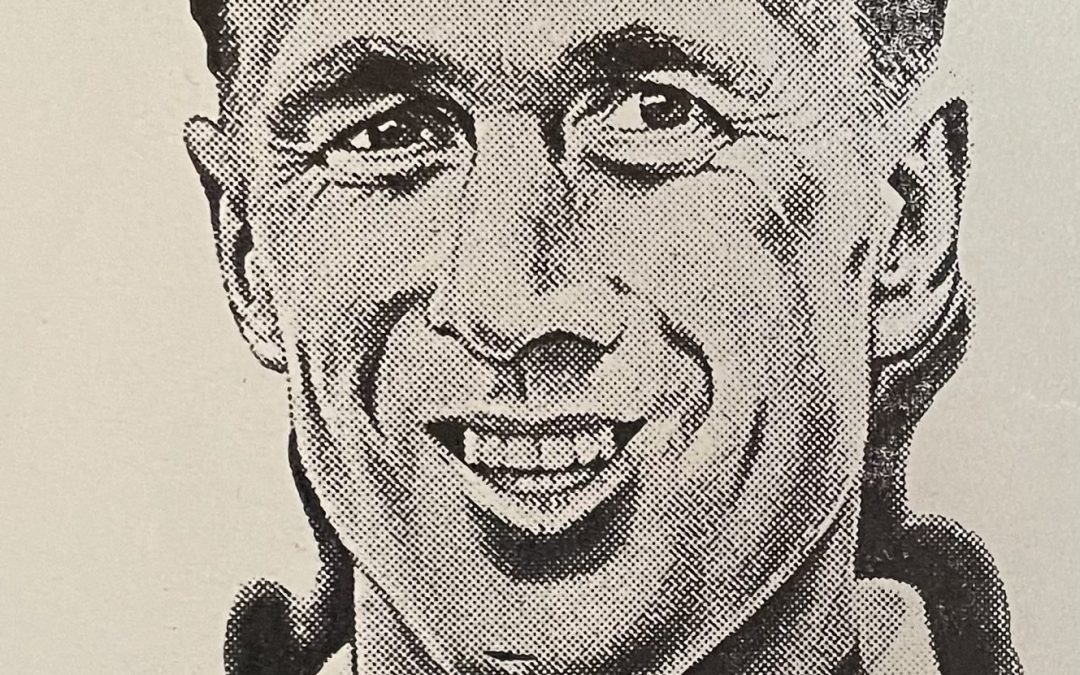

Joe leads England out against Scotland, led by Matt Busby

When the war was over Mercer returned to Everton, but things were clearly not the same. Secretary Theo Kelly had now taken over as manager and he accused the player of ‘not trying’ when captaining his country in a victory international against Scotland. England won the match 6-1 against a team skippered by good friend and army pal Matt Busby.

In fact, Mercer had suffered serious cartilage damage as confirmed by a specialist, and would need an operation. Kelly and Everton decided that, as the injury wasn’t suffered when playing for the club, the player would have to pay for the surgery himself.

This obviously caused friction and, hearing of the dispute, Arsenal stepped in with a bid of £9,000 for the player in December 1946. The deal was agreed and completed, with one final petty act by the Everton manager. The parties involved met at the Adelphi Hotel to conclude the transaction and Kelly arrived with Mercer’s boots therefore ensuring that he wouldn’t have the opportunity to return to Goodison to say goodbye to his teammates.

Joe was initially doubtful over the move south as he was reluctant to leave the family grocery store business. But the Gunners got their man after agreeing to allow the player to train in the north, travelling south only for games. He later justified his reasoning behind wanting to continue building the grocery business simply. “At that time I was making far more money in the grocery business than I could from football”. he said.

In footballing terms it was a simple decision for the player. “Everton told me I was a bad player”, he said at the time. “Arsenal told me I was a good one”.

It was certainly Arsenal who got the better of the deal. When Joe signed, they were second from bottom in the First Division having suffered a number of collapses from good positions. By the end of the season they had climbed to a respectable 13th.

Arsenal 1947-48

For the 1947-48 campaign, Tom Whittaker took over from George Allison as Arsenal manager and he immediately made Mercer captain. The pair led the team to the First Division title with a seven-point gap to Manchester United and with Everton way down in 14th. It was at Highbury that Joe’s leadership qualities really came to the fore. ‘You might be just about ready to drop,’ Denis Compton said, ‘but you never did – not with Joe behind you.’

One of the reasons behind Mercer’s renaissance was that Whittaker asked him to become a more defensive wing-half with his job focused more on breaking up opposition attacks and feeding the ball to the forwards rather than carrying it up the pitch.

Two years later he was leading his team out at Wembley and collecting the FA Cup after victory over Liverpool, the team he had, ironically been training with in the build up to the big match. He went on to be voted Footballer of the Year at the end on the campaign.

Joe with the Cup

After leading his team out at Wembley again in 1952 where, after playing most of the match with ten men following an injury to Walley Barnes they lost by a single goal to Newcastle, many thought that Mercer, now approaching his 38th birthday, might call it a day and focus on his grocery business.

He was persuaded to return for one more season and that decision was justified when he won his third title in all, and second as captain of the Gunners when they edged Preston North End to take the crown.

When the final day of the season saw the Gunners crowned as Champs at Highbury, the skipper made a speech. He said; “This has been the most splendid day of my life.

“But I am sorry to have to tell you that this is my last game for Arsenal. I am retiring from football”.

Footballer of the Year

After spending the summer contemplating his decision he decided to come back for one more campaign and eventually, the decision to retire was taken for him.

In April 1954 during a game against Liverpool, Mercer collided with Joe Wade. The Highbury crowd looked on in silence as Joe, his left leg hastily bound in splints, was stretchered off the pitch. Before long it was confirmed that he had suffered a double leg fracture bringing a long and distinguished career to a sad and abrupt end.

Although the injury seemed to surely signify the end of his career, his wife wasn’t so sure. “He will probably go on like this until he is a hundred”, Norah said, “and then take up blow football”.

But this time it was the end. Mercer focused on running the grocery business and also worked as a journalist but in 1955 he was given the chance to return to the game when Sheffield United offered him the manager’s job. Initially the new job didn’t go well. His first season at Bramall Lane saw the club relegated and he was unable to bring them back up.

Moving to Aston Villa in 1958 he suffered a similar fate to that with Sheffield United, being relegated from the top flight in his first year in charge. He put a good young side together at Villa Park and they won the inaugural League Cup in 1961 but in 1964 he suffered a stroke and was sacked after recovering.

Returning to full health, the next go at management proved the successful one. Joe took the reins at then-Second Division Manchester City and brought Malcolm Allison on board as his assistant with the number two providing innovative ideas as the pair built a team that both entertained and won.

Joe and Frank O’Farrell lead their teams out for the Cup final

After the pair took over in 1965 City added Mike Summerbee and Colin Bell (with Francis Lee joining a year later) and led the club to the Second Division title in 1966 and then the First Division crown in 1968. Then came the 1969 FA Cup win over Leicester City and the 1970 double of the League Cup in which they got the better of West Bromwich Albion in the final and the European Cup Winners Cup where Gornik Zabrze were beaten. That FA Cup win ensured that he became the first man to win both the league and the cup as captain and manager.

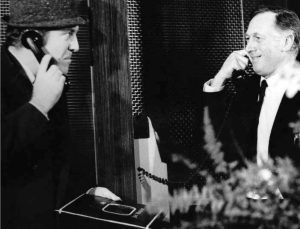

Eamon Andrews surprises Joe

In 1970 Joe was surprised by Eamon Andrews and his famous ‘big red book’ becoming a subject of ‘This Is Your Life’. It was a star-studded affair with the likes of former schoolmate Cullis, Dixie Dean, Matt Busby, Frank Soo, Walley Barnes, Raich Carter and Stanley Matthews appearing alongside the City team of the time to pay tribute.

Joe at Maine Road

In 1971 Mercer and Allison took different sides in an ownership battle at Maine Road. The group led by Peter Swales, and supported by Allison won the day and the former number two took over as Manager, with his ex-boss ‘moved upstairs’ in the General Manager’s role, effectively pushing him out of the major footballing decisions..

So Mercer moved on, to Coventry as General Manager. It was while he was at Highfield Road that he replaced Sir Alf Ramsey as caretaker England manager.

Joe took over as England boss at a difficult time with the country having suffered that shock World Cup elimination at the hands of Poland. His choice of players – he gave Keith Weller and Frank Worthington debuts and also included the likes of Stan Bowles – indicated that he wanted to put a smile back on the face of England fans. It worked but sadly the reign was temporary with Don Revie taking the helm permanently.

After quitting the Coventry job in 1975, he joined the club’s board of directors and served them until retiring in 1981. He was awarded the OBE for services to football in 1976.

Mercer suffered from Alzheimer’s during his later life and he passed away in 1990 on his 76th birthday.

Joe Mercer had to battle through many setbacks during his career. But he continually bounced back, and always did so with a smile on his face. The record of the man known as ‘Gentlemsn Joe’, as player, as captain and as manager truly stands the test of time.

In 2021 a plaque was unveiled in Ellesmere Port commemorating Joe’s achievements in the presence of Mike Summerbee and Peter Reid among others. In a touching act, the Mercer family regifted the tea set that the town had given the player to mark his successes on the pitch in 1950.