1871-72 F. A. Cup. Charles Alcock creates, then wins, The Little Tin Idol

BY Vince Cooper

EVERY major sporting tournament in the world owes a debt to the F.A. Cup, the first competition of its kind and still, over 150 years after its inception, perhaps the best known. That competition, therefore and the sporting world, are indebted to one Charles William Alcock.

That Alcock also organised the first England v Scotland international and was behind the first-ever Ashes test match between England and Australia surely earns him a unique place ant the top of anyone’s list of the greatest sporting innovators.

The Football Association had been formed in 1863 but for the first seven years clubs competed under its auspices against each other just in friendlies. Then Alcock, already becoming established as a noted player and administrator (and we’ll get back to him later) and secretary of the Association, came up with the idea of a Challenge Cup competition between members. Alcock, an Old Harrovian, would later say that he got the idea from the inter-house competitions that had taken place during his time at the school.

One of the first areas to be addressed was the trophy and Alcock wrote to all members proposing that ‘it is desirable that a Challenge Cup should be established’ asking for subscriptions to raise the £20 needed. The money (the equivalent to around £2,500 today) came in with Scottish members Queen’s Park among those to donate, pledging 1 Guinea (£1.05), and the creation of the trophy, which became known as the ‘Little Tin Idol’ was commissioned.

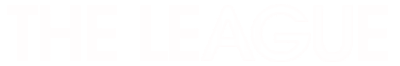

Stolen!

That first cup would last until 1895 when thieves removed it from a Birmingham shop window whilst in the care of then-holders Aston Villa who were fined £25 for losing it. The association then had a second trophy, an exact replica of the first, made.

The tournament was responsible for the creation of some of the rules that still exist to this day. For the first time, matches would last for 90 minutes and each team would consist of 11 players. But extra-time was still some way away, despite an early attempt by Wanderers to make it happen. If a match was drawn there would either be a replay or both teams would progress to the next round.

Although some rules remain from those days, many have been changed. Throw-ins were taken one-handed, teams changed ends each time a goal was scored and the players from the opposing teams were identified by the caps or garters they wore.

There was a disjointed entry in year one. 15 teams (out of a total F. A. membership at the time of just under 50) entered the competition and when the draw was made the wonderfully-named Hampstead Heathens were given a bye. This left seven matches of which only four were actually played.

Queen’s Park

The aforementioned Scots of Queen’s Park were drawn to meet Donnington School and as the pair couldn’t agree on a venue both were allowed to progress to the next stage. Two other teams, Reigate Priory and Harrow Chequers, withdrew giving their proposed opponents, Royal Engineers and Wanderers respectively, a bye.

So that left four matches which all took place on 11 November 1871. In these there were wins for Barnes who beat Civil Service, Maidenhead who saw off Marlow and Clapham Rovers whose 3-0 win over Upton Park included a brace from Jarvis Kenrick, one of which was the first-ever F. A. Cup goal. The fourth match, between Hitchin and Crystal Palace, finished goalless with both teams given a place in the 2nd round.

That left ten teams through to the 2nd Round which meant five matches.

When the draw was made Queens Park and Donnington were again paired. This time the Lincolnshire school withdrew, claiming that they couldn’t afford to travel to Glasgow and this sent the Scots through.

Of the four matches that were played there were easy wins for the Royal Engineers (known as The Sappers and lauded by many as the first English team to play passing football) who scored five times without reply at Hitchin and Crystal Palace whose second in their 3-0 success over Maidenhead was scored by Charles Chenery.

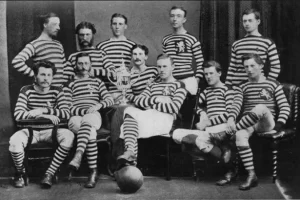

Scotland v England 1873. The England line-up features Charles Chenery and Walpole Vidal whilst the ‘Umpire’ in Charles Alcock.

Chenery would go on to play for England in the first-ever international against Scotland in October 1872 and make two further appearance for his country.

Wanderers recorded a single-goal victory over Clapham Rovers at Clapham Common whilst the other tie featured the first-ever replay. Barnes and Hampstead Heathens – who played with only ten men – were level at 1-1 in their first match when bad light stopped play.

This caused the competition’s first-ever replay, with Barnes again the home team. Again the Heathens had only ten players but they still managed to prevail by a solitary goal.

With five teams left in the competition the Scots of Queen’s Park were given a bye to the semi-finals thereby making it to the last four without kicking a ball, and after Wanderers took over Clapham Rovers’ Common pitch and fought out a goalless draw with Crystal Palace both teams were allowed to advance.

So, the only team of the five to be eliminated were Hampstead Heathens who lost 3-0 to Royal Engineers. The Heathens started the match at Chatham with just nine men and although one of the missing players arrived halfway through they were always at a disadvantage and The Sappers, led by Capt. Francis Marindin ran out comfortable 3-0 winners.

Captain Marindin

Marindin later became a referee and took charge of eight F. A. Cup finals whilst he also spent time serving as President of the Football Association from 1874 to 1879

Much like nowadays both of the semi-finals were played on the same ground with Kennington Oval the chosen venue and here again Charles Alcock was all over proceedings. In his position as secretary of Surrey County Cricket Club the 29-year-old offered the venue; in his role as secretary of the F. A. he unsurprisingly accepted.

At the first time of asking neither semi produced a goal. In mid-February the match between Crystal Palace and Royal Engineers finished 0-0. The teams met again three weeks later and the Army men came out on top 3-0 thanks to a pair of goals from Lieut. Henry Renny-Tailyour and one from Capt. Hugh Mitchell.

Both Renny-Tailyour and Mitchell would go on to play international football for Scotland although neither was born there. The first-named was born in India while his Scottish father was serving there and would go on to score his country’s first international goal in a 4-2 loss to England in 1873.

Mitchell was born in London where his Scottish-born parents were living and was joined in the Royal Engineers team by his brother-in-law Col. Edmund Cresswell who was also the secretary of the Sappers football team.

In early March Queen’s Park travelled down from Glasgow for their first match in the competition with a place in the final at stake and fought out a goalless draw with Wanderers. The match was tight with few chances at either end. Perhaps the best fell to none other than that man Alcock but he missed the target. At full time the Londoners offered to play an extra 30 minutes in an attempt to produce a winner but their Scottish opponents declined and promptly withdrew from the competition leaving Wanderers with free passage to the final.

Although it might have seemed a strange decision to refuse to play extra-time there was no animosity between the two teams and at a dinner held in the evening Queen’s Park were toasted and praised for ‘their enterprise and determination evinced in journeying so long a distance for the good of football’.

And so to the final, played at The Oval on Saturday 16 March 1872. Entry cost a hefty one shilling (5p) with the reported attendance of 2,000 kept down by what was regarded as ‘the advanced price charged for admission’.

Included in the Wanderers line-up was one ‘A. H. Chequer’ who was in fact Morton Betts. The pseudonym (meaning A Harrow Chequer) was used because Betts, who later went on to win one England cap, was originally registered to play in the competition for Harrow Chequers who had entered but then withdrew before their first round match, ironically against Wanderers, was played. Charles Alcock was also in the line-up as were fellow future internationals Reginald Welch, Alexander Bonsor, Charles Wollaston and the wonderfully-named Walpole Vidal.

Whilst Wanderers were thought to possess the more skilful individuals, the better teamwork of the Army side was expected to give them the edge.

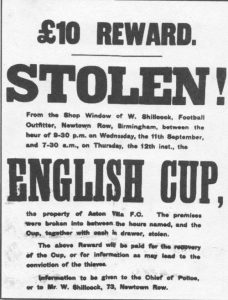

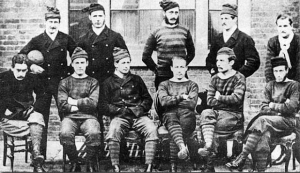

The Royal Engineers. Losing finalists

The Sappers who had been unbeaten for over two years included Capt. Marindin in goal along with their Scottish contingent of Renny-Tailyour, Mitchell and Cresswell.

Wanderers won the toss and chose to play with the sun at their backs and aided by a strong following wind. With just ten minutes gone Cresswell fell awkwardly and suffered what was later diagnosed as a broken shoulder. He bravely played on but was little more than a passenger for the remainder of the match.

Wanderers, effectively playing against ten men, unsurprisingly dominated and with 15 minutes gone the 18-year-old Vidal, still attending Westminster School at the time, broke clear. The man who would later become known as the ‘Prince of Dribblers’ and who would win the cup for a second time when playing for Oxford University two years later, went on a mazy run before sending a looping ball across the field. The ball fell kindly for A. H. Chequer (Morton Betts) who promptly sent it between the posts. So, the honour of scoring the first-ever Cup-winning goal went to a man playing under an assumed name.

After the goal was scored, the teams, as per the rules, changed ends but despite now having the worst of the conditions Wanderers continued to control the game. Alcock looked to have added a second but referee A. Stair of Upton Park rightly disallowed the effort for handball in the build-up and there were other chances with Capt. Marindin in The Sappers goal needing to be at his best to prevent the lead being increased.

Royal Engineers had been expected to finish stronger as they were thought to be the fitter of the two teams but with Cresswell ‘completely disabled and in severe pain’ according to a report in ‘The Sportsman’ they failed to impose themselves and Wanderers held on with little threat to their lead.

A winners medal

The ‘Little Tin Idol’ was presented to Wanderers a month later at their annual dinner and the victory also gave them a bye to the following year’s final where they retained the trophy with a victory over Oxford University despite Vidal, one of their stars, now being in opposition.

Taking Vidal’s place in the victorious Wanderers team a year later was the American Julian Sturgis who thus became the first overseas player to win the cup.

The clash of Wanderers and Royal Engineers was undoubtedly that of the two giants of early football. One or the other of the pair would play in the first seven Cup finals and they would meet again in the final in 1877-78 when Wanderers ran out 3-1 winners, but this was the last appearance at the ultimate stage for both.

Despite the presence of many great personalities in the initial tournament the one who stood head and shoulders above all others, and who undoubtedly had the biggest influence on football was Alcock.

Charles William Alcock was born on 2nd December 1842 in Sunderland. His father was a ship owner and Charles followed his brother John Forster Alcock in attending Harrow School.

By the time he left Harrow in 1859 the family had moved to Chingford in Essex with his father by now establishing himself in marine insurance. The brothers formed a football team, Forest FC along with other Old Harrovians and a number of Old Foresters (ex-pupils of Forest School) and in 1863 the club became Wanderers.

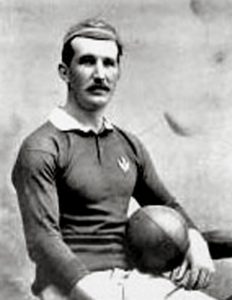

Alcock the player

The name of the club came about as they never officially had a home ground. Indeed they would play ‘home’ matches in various parts of London, stretching as far as Epping Forest in the east to Battersea Park in the south west and Crystal Palace farther south.

Having instigated the competition Alocock then skippered the winning team, which seems a little like the boy who brings the ball having first pick when it comes to choosing teams. He had already led England in five matches against Scotland which were deemed unofficial as only London-based Scots were included and he then issued a challenge in Glasgow and Edinburgh newspapers which led to the first official clash between the ‘Auld Enemy’.

That match took place on 30 November 1872 at Hamilton Crescent, Partick and finished in a goalless draw and although Alcock didn’t play then, he captained the national team, and scored, in a 2-2 draw in 1875.

He also refereed two cup finals and retained his position as secretary of the F. A. until 1895, overseeing the integration of Northern teams into the association and also the introduction of professionalism.

Alcock (right) with W. G. Grace

Also a first-class cricketer, Alcock skippered Middlesex in the first-ever county match before appearing for Essex and then becoming secretary of Surrey. In this capacity he arranged the first-ever test match between England and Australia at the Oval in 1880.

Alcock in his office

Although a noted journalist, writing and publishing the Football Annual for 40 years as well as James Lillywhite’s Cricket Annual, it is Alcock’s work as an administrator and creator of three of sport’s major competitions that earns him a position as the ‘father’ of organised sport as we now know it.

The second ‘Little Tin Idol’ was bought by then-Birmingham City and later West Ham United owner David Gold at auction in 2005. He loaned the trophy to be displayed at the National Football Museum in Manchester and when he put it up for auction in 2020 it was bought by Manchester City owner His Highness Shiekh Mansour bin Zayed who loaned it back to the museum where it is now on display as part of the permanent ‘FA Cup exhibition’.

So, the FA Cup certainly had humble beginnings but with the help of it’s many passionate supporters over the years, kicking off with Mr Charles Alcock, it will never relinquish its place as the greatest and most-storied sporting trophy in the world.

*The trophy pictured in this article is the replacement*