By Vince Cooper

Since it’s inception in 1872 the Football Association initially decided to keep final of the FA Cup in the south. Kennington Oval was the preferred home (with one ill-fated trip to the Lillie Bridge Ground in West London) and the only time the destination of the trophy was decided outside of London was when the 1886 final went to a replay which was played at Derby’s Racecourse Ground.

In 1893 the Surrey County Cricket Club informed the FA that, due to re-turfing, the Oval would not be available for that year’s final – although it actually staged another, smaller Cup final on the same day. Pressure from the – mostly Northern – members of the Football League forced the FA to look North for a new venue for the competition. The days of the competition’s later stages featuring Universities and Old Boys teams were in the past and it was decided that the Manchester Athletic Ground at Fallowfield, opened in 1892 and having already staged the Lancashire v Yorkshire rugby match, would be up to the task of putting on football’s showpiece game.

After the contestants for that year’s competition were whittled down to 32 thanks to preliminaries, the 1st round proper took place on the 21st of January with only two Southern teams still involved. When the round was over there were none.

Royal Arsenal made the long trip to current league champions Sunderland, who would go on to capture the title again and were thrashed 6-0 whilst fellow North Londoners Casuals, the team who would later merge with Corinthians fared only slightly better losing 4-0 at Nottingham Forest.

The most controversial match of the 1st Round was the clash between The Wednesday and Derby County. The match was initially played at Wednesday’s Olive Grove ground and the home team won 3-2 after extra time but County objected on the grounds that Wednesday fielded an ineligible player. The FA upheld the appeal and ordered that the match be replayed. Nine days later they met again with home team County running out 1-0 winners, again after extra time thanks to a goal from John Goodall sent the home team through. Or so they thought; this time Wednesday objected that Steve Bloomer had broken the laws of professionalism by signing contracts with both County and Bolton Wanderers and it was again upheld so the teams met for a third time without Bloomer playing. Finally three days later Wednesday, who were drawn to play at home ran out 4-2 winners at the third time of asking and although Derby appealed once again. It was denied and the Sheffield club went through.

The Wednesday also made it through the next round seeing off Burnley by a single goal but their run came to an end at the quarter-final stage when losing 3-0 at Everton’s new Goodison Park ground. The club had been forced to leave their Anfield home in the summer of 1892 and hastily set up home across town. They were drawn at home for each match until the semi-final and saw off holders West Bromwich Albion and Nottingham Forest before overcoming Wednesday.

Elsewhere in the quarter-finals champs-to-be Sunderland lost 3-0 at Blackburn Rovers and Wolverhampton Wanderers continued their progress, hammering 2nd Division Darwen 5-0. Wolves had already seen off Bolton Wanderers and Middlesbrough and were now matched with Blackburn in the last four.

In the other semi-final Everton were matched with Preston North End who saw off plucky Middlesbrough Ironopolis in the last eight.

Ironopolis had already seen off Marlow and Notts County to reach the last eight and, on a 25-game unbeaten run since September would surely have quietly fancied their chances at their Paradise ground. In front of 15,000 fans ‘the Nops’ took the lead early on through Hill. The visitors turned things around with two goals before half-time, from Gordon and Russell. In the second-half the home team fought back again and a goal from McArthur grabbed an equaliser.

The teams replayed at Deepdale and this time class told with Preston running out 7-0 winners.

So Everton faced Preston at Bramall Lane and teams drew 2-2. The second meeting, at the same ground, also failed to separate the teams as they both failed to score. The second replay was at Ewood Park and Everton finally made it through at the third time of asking, by two goals to one with Scot Patrick Gordon grabbing a late winner

The second semi-final saw Wolves take on Blackburn at Trent Bridge. Rovers went in front early on but Joe Butcher soon equalised and Robert Topham got the winner to send the Black Country club to the final.

So the final was set and the teams would do battle at a new ground. The FA’s comment on their value choice was that they had made their decision on a Northern venue to ease traffic problems caused by fans of the finalists being forced to travel down to London.

The Manchester Athletic Company had assured the FA that the ground could comfortably hold 50,000 fans. But many insisted that 15,000 was a more reasonable estimate and the lack of banking would mean that, even at the lower number, many would not enjoy a good view of the match.

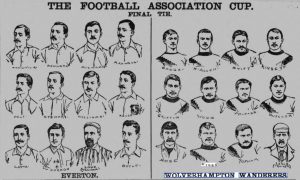

The final took place on 25 March and both teams put out the same eleven that had done battle for them in the semi.

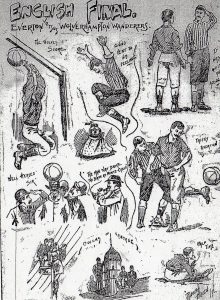

The ground started to fill from 11am. At 2pm a schoolboys match between Manchester and Sheffield took place with the local team running out 2-1 winners. Then, shortly before the main protagonists were due to take the field a fence broke on one side of the ground and hundreds of fans spilled onto the running track that surrounded the pitch. Quickly the track became full as spectators left their original position in search of a better view. There were a number of altercations as fans fought for a better view and ‘missiles were thrown’.

Wolves who had reached the final four years before, losing to Preston’s ‘Invincibles’ were first onto the pitch allaying rumours that they had refused to play because of the crowd troubles, followed shortly after by their opponents who were making their first appearance in the final The teams had met a week before the final in a league match where Wolves, fielding a much-weakened side, succumbed 4-2 to an Everton side who were in the midst of a run of four games in 10 days.

The early pace of the play was frantic with both teams creating chance. Everton’s Alf Milward found the net for his team halfway through the first half but the goal was disallowed because of a foul in the build-up and at the interval it remained scoreless.

Fans again spilled on to the pitch during the break and the start of the second period had to be delayed while they were cleared.

The game’s only goal came after an hour when Wolves skipper Harry Allen (above) tried a speculative long-range shot which goalkeeper Richard Williams allowed to slip through his hands. Everton tried to counter but the Molineux men held on comfortably and at the final whistle several of them ‘turned somersaults; to celebrate their success.

Everton skipper Bob Howarth complained before the game ended that fans encroaching onto the pitch were making it difficult to play and the club followed this up after with an official complaint which they later withdrew. Howarth would later say that he only protested because he thought Wolves had done so.

So it was Allen who went to collect the trophy (in the clubhouse) but the England international’s life would come to a sad end not long after.

The five times capped centre half had joined Wolves from Walsall Swifts in 1886. He played just over 150 times for the club before being forced to retire due to a persistent back injury just 18 months after the final. Within a year he was dead, after suffering from consumption, aged just 29.

More tragedy was to strike the Allen family just a few months later when Harry’s two-year-old daughter Beatrice Ellen was killed in a house fire.

Estimates of the crowd at the match varied wildly with some putting it at 30,000 whilst others suggested 60,000. The official figure was given as 45,000 but with fans leaving before the match even started due to the trouble and others replacing them it is difficult to be accurate. With a capacity far below this many fans had little view of the action.

In 1894 the final was moved to Goodison Park and then it returned south, finding a new permanent home at the Crystal Palace, partly because southern influence was now on the rise again and also no doubt because it gave the match a better chance of royal patronage, and gave visitors the opportunity of a trip to the capital.

So, the Fallowfield experiment lasted for just a single season. Whilst the stadium stage Rugby League Challenge Cup finals and even a Rugby Union International between England and Scotland big football returned just once. The 1899 FA Cup semi-final second replay between Liverpool and Sheffield United was staged there but had to be abandoned at half time due to persistent crowd invasions.

That was it for football and Fallowfield. The stadium continued to host top class athletics and cycling events (including being used for the 1934 British Empire Games) but it slowly began to fall into disrepair. Bought by Manchester University in 1960, the stadium was eventually demolished with a Halls of Residence being built on the site as part of the Fallowfield Campus.

Old Trafford has staged numerous big matches – including the replay of the 1970 FA Cup final between Chelsea and Leeds United whilst Maine Road hosted cup semi-finals and two England internationals. But if anyone asks you where the FA Cup was first fought for in Manchester answer Fallowfield. They might be surprised but you’ll be right!