IN 1874 the Reverend Thomas Ogden, the schoolmaster at Christ Church decided to form a football team which he named Christ Church F.C. Three years later the club and the vicar had a dispute over charging admission fees and the club went their own way, changing their name to Bolton Wanderers.

The Wanderers

The ‘Wanderers’ suffix in Bolton’s name came from the club being initially unable to find a permanent home, having used three different venues in their first four years of existence.

The club’s first permanent home was Pikes Lane which they moved into in 1881. After moving into the new ground they spent £150 on pitch improvements.

It was at Pikes Lane that Wanderers kicked off as one of the 12 original members of the Football League in 1888. And it was here that the first ever football league goal was scored with Kenny Davenport netting for Wanderers against Derby County at 3:47pm on 8th September 1888. This only became apparent recently when researchers discovered that the match between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Aston Villa, where a goal was scored after 30 minutes, had in fact kicked off at 3:30.

An ever-present in that first season, Davenport also went on to become the club’s first England international when playing in the 1-1 draw against Wales at Blackburn in 1885.

By the early 1890s Wanderers had decided that they needed a new custom-built home and the club organised a share issue in order to raise funds for the planned stadium. Thus, in 1894 Bolton Wanderers Football and Athletic Club was born and £4,000 was raised to build the new stadium.

Off to the Final

On the pitch 1894 saw the club’s first appearance in the FA Cup Final. They battled past Stockport, Newcastle United, Liverpool and The Wednesday to make it to the final but succumbed 4-1 to Notts County at Goodison Park in front of 37,000 fans.

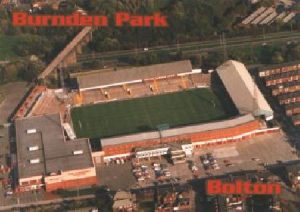

The site was chosen in the Burnden area of town, a little south east of the city centre, land was leased at £130 per annum and construction began. In 1895 the club moved into their new home and kicked off with a benefit match against Preston North End before 15,000 attended the first league match, a 3-1 win over Everton.

The 1898-99 season was the first to feature automatic promotion/relegation in the football league and Bolton suffered the fate immediately, being relegated alongside The Wednesday after finishing four points adrift of closest rivals Sheffield United. But they managed to bounce back the following season finishing runners-up to the Wednesday as both relegated clubs regained their position in the top flight.

In 1901, Burnden was chosen when a replay venue was needed after the FA Cup final between Tottenham Hotspur and Sheffield United at Crystal Palace finished all square. Over 22,000 were on hand to see the second clash as the Londoners overcame their more fancied rivals to become the first – and only – non-league club to win the trophy.

Ten years after their own previous run to the FA Cup Final, Wanderers reached a second in 1904. This time they travelled down to Crystal Palace but they lost out again, this time by a solitary goal to Lancashire rivals Manchester City.

In 1904 there were more stadium improvements. The Manchester Road (Main) Stand was constructed and the following year the Great Lever End was terraced and covered over. Both of these works were carried out by local company John Booth who also did most of the steelwork for Wembley Stadium. During this period the stadium was also featured in films made by documentary pioneers Mitchell and Kenyon (many of which are still available).

Smith’s Arrival

The club’s League form continued to show inconsistency with three more relegations until 1911 when they returned to the top flight and remained for 21 years. One of the major early reasons for the upturn in form was the arrival from Crewe Alexandra of forward Joe Smith. Smith never made an appearance for his first club and joined Wanderers in 1908. He stayed for 20 years and scored over 250 goals, holding the club’s scoring record until he was surpassed in the 1950s by the legendary Nat Lofthouse.

Smith might well still hold the scoring record were it not for the First World War, which robbed him – and Wanderers – of six prime seasons. In the lead up to the War he finished top scorer in three season out of four, and once peace returned he kept on scoring, breaking the club’s record in 1920-21 with 38 goals. Throughout the rest of Smith’s time at the club the Trotters consistently finished in the top six and he also had the honour of leading them to undoubtedly the greatest day in their history.

The First Wembley Final – Bettering the Hammers

On 28th April 1923 Smith led Wanderers out to face West Ham United in the first FA Cup final to be played at Wembley Stadium. We will never know how many were at the match but it was certainly way above the official attendance of 126,047 and probably closer to 200,000. There were chaotic scenes inside and outside the stadium, but Bolton did not let the occasion get to them, running out 2-0 winners with goals from David Jack and Jack Smith.

It was David Jack, who had returned to his hometown to play for Bolton from Plymouth in 1920, who took over as the main man. Wanderers made it to Wembley twice more in the 20s. In 1926 Jack scored the only goal as they squeezed past Manchester City.

In 1929, after Jack had left for Arsenal, Wanderers took the cup again as goals by Billy Butler and Harold Blackmore saw them overcome Portsmouth. Three Wembley visits, three clean sheets for goalkeeper Dick Pym who made a total of 301 appearance for the club.

There were further ground improvements too. In 1928 the Burnden Stand was built with a paddock area at the front and over 2,500 seats in a raised area at the back.

‘Mass Observation’

After the earlier Mitchell-Kenyon filming Burnden was again held up as an example of the ‘typical’ football stadium in the 1930s when Humphrey Spender part of the famed ‘Mass Observation’ group created ‘Worktown’ a documentary series of photographs of everyday life which including shots of matchdays in and around the stadium. In doing so he provided yet another example of how well dressed the average football fan was in those days.

During this time, the football those people were watching was, in truth, nothing to get excited about with a short spell in the second division a particular low point. Perhaps the highlight in the 1930s came with an FA Cup 5th round tie with Manchester City which saw 69,912 pack the stadium.

The war years for Bolton were perhaps most notable for the debut of local lad Nat Lofthouse who would go on to define the club over the next two decades. Then, the immediate post-war period was dominated by a tragedy which shook the football world.

The Disaster

On 9th March 1946, Bolton entertained Stoke City in the FA Cup 6th round. For that season, with no official league football, it was decided to play Cup ties over two legs in order to increase the number of games played and therefore add to revenue. Wanderers had won 2-0 at City a week before and it is estimated that over 85,000 tried to cram themselves into the ground.

The turnstiles on the Railway Embankment side had been closed since 1940 and this forced the 28,000+ supporters making their way there to enter through the Manchester Road end turnstiles. Fans holding tickets for the Burnden Stand had to be admitted through the main stand and then escorted to their area. The gates were closed 20 minutes before kick-off but fans scaled the walls, climbed over the closed turnstiles or crossed the nearby railway line to enter and, eventually, many walked in after one of the gates was unlocked. Fans found themselves forced all the way around the pitch with many ending up out in the car park where they were unable to watch the game.

Many of the facilities very basic and the Railway End was nothing more than a bank with some flagstone steps. There would have been more room in the stadium but the Ministry Of Supply had requisitioned part of the Burnden Stand during the war and it had not yet been restored to its normal use. This meant that 2,789 seats were not available.

Shortly after kick-off fans spilled onto the pitch and the game was stopped for a short while. After the restart a policeman went onto the pitch and talked to the referee George Dutton. Nat Lofthouse later said that he overheard the policeman say; “I believe those people over there are dead’. Two crush barriers had collapsed forcing fans on top of each other.

The referee called the two captains, Harry Hubbick and Neil Franklin, together and after a short discussion the players left the pitch. The dead and injured were taken from the Railway End terrace with the dead covered in coats and laid along the touchline and a new line marked out with straw. Incredibly, half an hour after leaving the pitch the players returned and continued the game. At half-time the teams changed ends and immediately started the second half. Stanley Matthews, a member of the Stoke team that day, later said that he was ‘sickened’ by the decision to finish the game.

33 died and over 400 were injured in the disaster and in its aftermath a public enquiry was ordered and carried out which recommended more rigorous control of the number of spectators allowed into games. Many, including local police and representatives of the club, blamed fans for the tragedy but there were certainly many factors involved including a serious underestimation of the amount likely to attend, the after-effects of the war and the various difficult and unprepared conditions at the ground, and in fact of all grounds. The famed football writer Clifford Webb, writing in the Daily Herald said; “Plans should be in preparation now, especially in blitzed areas, for the complete remodelling of grounds. Football has outgrown the ramshackle, rusty affairs ironically named ‘grand stands’ and the weedy unterraced banking”.

The disaster is remembered with two memorials; One at the original site and one at the club’s new home, the Macron (formerly Reebok) Stadium.

Perhaps unsurprisingly in the years after the disaster Bolton struggled. Despite the presence of the Lofthouse, ‘Lion of Vienna’ it was a period of mediocrity for the team, the only highlight being the 1953 FA Cup where they seemed all set to claim the trophy before the intervention of Stanley Matthews and Stan Mortensen of Blackpool. Lofthouse won Footballer of the Year at the end of that season and he continued to lead his only club throughout the decade, finally being rewarded with the major trophy his talents deserved in 1958.

Nat Brings Glory Back

In the FA Cup Wanderers overcame Preston at Deepdale before home wins over York City (after a replay), Stoke and Wolves led to a 2-1 Maine Road semi-final victory over local rivals Blackburn Rovers. In the final two goals from Lofthouse earned the win over a Manchester United severely depleted by the Munich disaster three months before.

The Bolton team that day included only two players, Doug Holden and Lofthouse, who had played five years before against Blackpool, and not a single member of the side had cost a transfer fee.

‘Going To The Match’

Following on from its depictions by Mitchell and Kenyon and in the Worktown project Burnden Park continued to feature prominently in the arts as the archetypal ‘old school stadium’. The 1953 L.S. Lowry painting ‘Going To The Match’ (originally entitled ‘Football Ground’) depicted the scene outside the ground while in the 1955 movie ‘The Love Match’ Football-mad locomotive driver Arthur Askey stops his train outside the stadium to watch the match from the bank. The Railway Stand also features in the 1962 movie ‘A Kind Of Loving’.

By the early 60s both Burnden Park and Bolton Wanderers were in decline. With Lofthouse gone the team fell out of the top flight, despite continuing to discover top young players like Francis Lee and Wyn Davies. In the early 70s the club spent a couple of seasons in the third tier before a mini renaissance as they continued to produce some fine players only to see most lured away to greener pastures.

The decline of Burnden continued and in 1986 part of the Railway End was sold and developed as a retail superstore. Finally in 1997 the club decided it was time to move and Burnden was sold and redeveloped as a retail park.

One Last Hurrah

But there was time for one last Burnden hurrah before Wanderers finally left. With Colin Todd at the helm the team romped to victory in the First Division, winning the title by 18 points, scoring exactly 100 goals and earning promotion to the Premier League. 21,880 turned up for the last match at the old ground, a 4-1 win over Charlton Athletic on 25 April 1997.

And so it closed on a happy note. Whilst any history will always be clouded by the tragic events of 1946, there is much, on film, in art and in photography to ensure there are many other, brighter aspects of Burnden Park that will also never be forgotten.