BY Vince Cooper

If you look up the word ‘Corinthian’ in a dictionary you’ll find two definitions. One relates to natives of the ancient region of Corinth in Greece and the second is ‘involving the highest standards of amateur sportsmanship’. It is the second definition that aptly describes Vivian Woodward.

The notion that a player could compete at the very highest level whilst pursuing a career elsewhere, and not receive a penny for playing the game seems laughable today or at least a product of bygone fiction. Woodward’s story is surely one straight from ‘Boy’s Own’ comics. The only surprise is that it really did happen.

Born close to the Oval cricket ground in Kennington on the 3rd of June 1879 and the seventh of eight children to a comfortably-off middle-class family, Vivian John Woodward was always a football lover. But father John, an architect and surveyor, and a Freeman of the City of London, insisted that young Vivian concentrate on his studies and devote any sporting time to his own loves, cricket and tennis.

Clacton Town 1900 with Vivian to the left of the trophy.

Despite his father’s misgivings, Woodward, whose family had by now moved out of London to the then middle-class area of Clacton-On-Sea, refused to stop playing the game he loved and, perhaps helped by the fact that his dad still spent most of his time in London, he played more regularly and soon became the star of the team at Ascham College, the private school he attended along with older brother Alexander.

Woodward’s first taste of ‘senior’ football was with Clacton Town of the North Essex League who had been founded by his former head teacher at Ascham. He quickly became their star, helping his side to victory twice in the 2nd Division of the North Essex League as well as a win in the 1900 Essex Junior Cup. The local ‘Clacton Graphic’ reported that the 20-year-old was ‘the backbone and centre of attraction in the team’.

Unsurprisingly Young Vivian started to receive offers from bigger clubs but he refused to turn professional, preferring to focus on following his father into architecture. After turning out briefly for Harwich and Parkeston and Chelmsford Town, he finally agreed to move up, joining then-Southern League Tottenham Hotspur on amateur terms in 1901, but insisted when signing that his ‘real work’ came first and indeed, he missed several matches for the club because of work duties.

When he did play it quickly became clear that this was a rare talent. A swiftness of both mind and body put him and his team one step ahead of opponents and an ability to snap up any glimmer of a scoring chance soon had him rattling in the goals.

Woodward made his Spurs debut against Bristol City in the Southern League on the 6th of April 1901. It was a match where his team rested most of their first-choice players with an F. A. Cup semi-final two days hence but they managed to beat a City side who were still in the running for the title at the time 1-0.

He would miss the start of the next and indeed most seasons due to commitments with work and with the Spencer Cricket and Tennis Club and Spurs announced that he would play for them ‘whenever it is convenient’. Despite repeated overtures, he steadfastly refused to turn professional throughout his career and indeed would not even claim travel expenses from the various clubs he played for.

An appearance for the South against the North in a trial match brought him to the attention of many, including one Football League club Secretary who is said to have remarked: “I would like to put Woodward in my bag and take him away”.

Despite missing so many games, Woodward’s ability, and his display in that trial match led to him winning his first England cap in February 1903, scoring a brace in a 4-0 win over Ireland. After the win one journalist memorably called him ‘The human chain of lightning, the footballer with magic in his boots’. He would go on to win 23 caps for his country’s professional team (despite never being a pro himself), 14 of them as captain and scored 28 goals, a phenomenal strike rate and a total which would remain a record until broken by Tom Finney 55 years later.

The same journalist went on; ‘Woodward is a great initiator, the personification of unselfishness, quick to grasp the ever-changing situation of a game and above all, is very cool’

Described at around the same time by the Sporting Chronicle as having; ‘A subtle craft tucked away in his toes’, Woodward spent parts of nine seasons at White Hart Lane, had the distinction of scoring their first-ever league goal and of playing a huge role as the club made their way into the 1st Division.

Woodward’s skills on the pitch were matched by his demeanour, and indeed the ‘Corinthian’ (that word again) nature of his play. One of the most acclaimed football writers of the day, J. H. Catton who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Tityrus’, said of him: “He was one of the most modest of men, and one of the most charitable.

In action against Scotland at Bramall Lane in 1903

“Only once did I hear him criticise the conduct of another man. I felt sure that this person deserved more than the mild censure passed upon him because a harsh remark was so foreign to Woodward’s nature.

”He had a great contempt for people who engaged in rough play, because he was the fairest fellow who ever put a boot to a ball. Much was required to arouse him to resentment because his game was all art and no violence”.

Spurs and Everton in Vienna

At the end of a 1904-05 campaign in which he had top-scored for Spurs with 14 goals Woodward was part of the squad that went, along with Everton, to play in a number of exhibition matches in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The first match saw a 6-0 win over a local team in Vienna which Woodward and player-manager John Cameron missed, but both were there for the clash with Everton for the ‘NWT Cup’. The Toffees won that match 2-0 in front of the biggest crowd ever for a match in Vienna (variously reported as between 7,000 and 10,000) and both teams attended a banquet in the evening which reportedly ‘took a very animated course’.

A third game in Vienna saw a 4-1 win over Wiener Athletic Club with Woodward scoring twice, and then it was on to Budapest and Prague. They won three of the four matches but lost perhaps the most important when Everton beat them for the second time, recording a 1-0 win in Prague.

That wasn’t the end of Woodward’s travels in 1905. He missed the first three months of the 1905-06 English season as he was busy touring the United States and Canada as part of the Pilgrims team.

The Pilgrims were an amateur team financed by American businessman C. H. Murray and created to raise interest in the game in both America and Canada. Fred Milnes of Sheffield United was skipper and he, along with Woodward was scheduled to meet President Roosevelt, a fan of the game although sadly the meeting never happened.

The Pilgrims played a total of 17 matches in Montreal, St Louis, Chicago and New York among other places. They won 14, drew one and lost two in 45 days.

The Pilgrims in New York

At The Polo Grounds in New York the team attracted a crowd of over 4,000 who saw them beat a team of ‘All Stars’ 7-1.

Another continental trip with Spurs would follow at the end of the 1906-07 season when they played and won twice in Belgium including a 2-1 victory over Southern League champions Fulham. Woodward scored three times in the two matches.

The Great Britain Olympic team 1908

In 1908 Woodward was chosen as captain of the Great Britain team (actually an England Anateur team) at the London Olympics, the first time the sport was included in the games.

The skipper scored twice in the opening match, a 12-1 hammering of Sweden but left the scoring to Glossop North End’s Harry Stapley in the semi-final, the former West Ham man getting all in a 4-0 success over the Netherlands.

Great Britain took on Denmark in the gold medal match and recorded a 2-0 win. Centre-half Fred Chapman of South Notts opened the scoring in the first-half and Woodward added a second just after the break to clinch the win in front of a crowd of 10,000.

At the start of the 1909-10 season Woodward decided to retire from the game to concentrate on architecture and devote any sporting time to cricket. However, he couldn’t stay away, quickly coming back and making a few appearances for Chelmsford.

In November 1909 as Chelsea struggled near the foot of the table manager David Calderhead, with his team bedevilled by an injury crisis, persuaded Woodward to move to Stamford Bridge. Spurs were also interested in re-signing their former star but the forward had his own reasons for moving to West London.

There have been many reasons for players to switch clubs over the years and some interesting ones between Chelsea and their North London rivals but Woodward’s probably ranks near the best. He said: “The short bus-ride from my home to Stamford Bridge was so much more convenient than the trek across London”.

It might well have been that part of Calderhead and the club’s reasoning behind the signing was to bring a different culture to the dressing room. Woodward was obviously known as a sporting type who clearly played purely for the love of the game and who was also a confirmed teetotal. He was joining a Chelsea team who had a reputation for their cavalier approach to training and with a drinking reputation (one player had allegedly been suspended for punching a cab horse while drunk).

But it was in order to help rectify injury woes that Woodward accepted the new assignment. The Blues’ matchday programme, ‘The Chelsea Chronicle’ after bemoaning missing players (they had an entire forward line out injured), and ‘bad luck’ lauded the new arrival saying; ‘There was many a glad smile round the regions of Stamford Bridge when it was announced that Vivian J. Woodward has thrown in his lot with the Chelsea Club’.

The player was, in fact, honouring a promise made to Chairman Claude Kirby three years before when he said that if ever he was a freelance he would ‘come to Chelsea if they thought I could be of any service to them’.

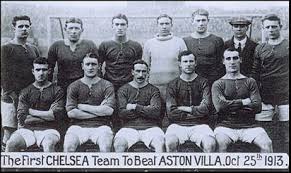

In the Chelsea team

His arrival at Stamford Bridge actually meant a top flight debut for Woodward but he started with a 4-1 loss at Sheffield Wednesday. The following week his home bow produced a much better return with a 4-1 win and a brace for the new man. But he was missing the next week, busy scoring six times for the England amateur team in a 9-1 win over Holland as Chelsea lost 4-2 at Bury. The remainder of the season saw some great wins including a 2-1 victory over champions Newcastle where he scored the winner but also bad losses (many coinciding with the new star’s absences through international or work commitments, or because of injury) and they dropped into the second tier at the end of the campaign.

Having initially only agreed to play for the club until the end of the season, Woodward, with a clear determination to help them regain their top-flight status, agreed to stay on.

The Blues would spend two seasons in the 2nd Division, missing out on promotion by two points in 1910-11 in a campaign which also saw a run to the F.A Cup semi-final.

Late in that season Woodward suffered a broken arm in a match against Derby County, this would keep him on the sidelines for the early part of the following campaign but he came back with a bang.

He inspired the Blues back to the top flight, but not without some last day drama. The Blues took the field on the final day knowing that even a win against Bradford Park Avenue might not be enough. They were level in 2nd place with Burnley but with an inferior goal average so victory might not prove enough.

Chelsea did their part, beating their Yorkshire rivals with a solitary Charlie Freeman goal and when news came through that their rivals had lost their final match the 30,000+ crowd went wild. Woodward, the biggest influence merely said; ‘Well done, chaps’ to his teammates and went back to his architect’s desk.

The amateur star continued playing a major role as the club survived the 1912-13 campaign, ending the season as top scorer as the Blues finished a solitary place above the relegation spots, five points clear of Notts County and 10 ahead of Woolwich Arsenal.

For Woodward 1912 also brought a second Olympic title. He carried the flag in the opening ceremony and led Great Britain to gold in Stockholm. The star scored two of his team’s 15 goals as they secured the top spot by again beating Denmark, led by soon-to-be clubmate Nils Middleboe, 4-2 in the final.

Chelsea’s last game of the 1913-14 season was a 2-0 home win in over Everton in front of 30,000 at Stamford Bridge, a result which saw them finish the season in a fine 8th place. The attendance was on the small side considering that earlier in the campaign crowds had reached as high as 58,000 for the visit of Aston Villa and a whopping 61,500 for the opening-day loss to Spurs.

The team looked well set for a sustained effort in the upper reaches with the arrival of more top players in the shape of double title and F.A Cup winner Harold Halse, one-eyed striker Bob Thomson and the aforementioned Middleboe. It looked like top honours might be just around the corner.

What actually lay ahead for the club was a first F.A Cup final appearance in the ‘Khaki Final’ whilst what lay ahead for the country was the four years and four months of bloody conflict of the Great War, in which Woodward would play a significant role.

Chelsea had reached their first final by seeing off Swindon Town, Woolwich Arsenal, Manchester City, Newcastle United and Everton. Woodward was already in uniform by then and raising cups of tea to salute the victories from afar rather than playing a part in them.

Having played his last amateur international against Sweden in June 1914, he finished with a record of 57 goals in 44 amateur internationals, and joined the 1/5th City of London Battalion of the London Rifle Brigade as soon as war broke out. Three months later Woodward applied for a commission and was transferred to the 17th service Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, the famed ‘Footballers Battalion’ as a second lieutenant. The joining up of Woodward and his ilk did much to encourage football followers all over the country to take up arms.

Woodward managed to play in some games during the 1914-15 season and was given special permission to travel to Manchester for the final against Sheffield United.

Bob Thomson had been playing at centre-forward during the cup run but was a doubt for the final due to a dislocated arm and it seemed that Woodward might take his place with the club directors pleading with him to play.

When Thomson was declared fit however, Woodward, true to his nature, refused to take part, insisting: “Bob helped to put Chelsea in the final, so he deserves to play”. The Blues, with their star man watching from the stands, lost 3-0.

The Footballers Battalion – Woodward third from left in the front

Woodward went back and rejoined his Battalion after the game and was soon promoted to captain.

In 1916 the ‘Footballers Battalion’ reached the front line and there were soon casualties, with Woodward hit in the leg by a hand grenade which saw him sent back to England to recover. However he was back on the front line later that year, surviving a gas attack at the Somme which killed 14 men, and stayed until March 1917 when he was sent home to be schooled as a Physical Training Instructor in Aldershot but in 1918 he was back in combat action yet again, this time with the First Army.

After the Armistice, Woodward became coach of the British Army football team and in 1919, approaching 40 years old he played centre-forward and scored as they recorded a 3-2 win over France in the final of the ‘Inter Theatre-of-War Championship’ at Stamford Bridge.

At Stamford Bridge before playing for the British Army

Whilst Woodward’s playing career was over at the end of the war (although he did make one more appearance for Chelsea in a Charity match for the families of soldiers in 1920) his involvement with the club wasn’t. In 1922 he joined the board and would go on to spend eight years as a director before resigning.

He also retired from his architectural business at the same time, perhaps his most memorable achievement in this area being designing the main stand at Antwerp Stadium. After this he went on to run his own farm and dairy business in Weeley Heath near Clacton in Essex

.

.

‘Man Soccer forgot’

Woodward again served his country in the 2nd World War, this time as an Air Raid Warden. In 1949 he was taken ill, suffering from ‘nervous exhaustion’ and moved into a nursing home run by the F. A. in Ealing. He was visited there by a journalist and a former soldier who served under him in 1953 and the journalist, Bruce Harris, described him as: “bedridden, paralysed and infirm beyond his 74 years”.

And clearly lonely. “No one who used to be with me in football has been to see me for two years”, he told Harris. “They never come – I wish they would”. He passed away aged 74 in 1954.

Vivian Woodward was a key figure not just in Spurs and Chelsea’s history but in that of English football. As an international goalscorer for his country there is no equal. Counting goals for England at both professional and amateur levels the total is an astonishing 86.

Even more than his skills on the pitch, Woodward’s rush to serve his country at the outbreak of war perhaps meant even more, by encouraging many others who had followed his playing exploits to do the same. As such, he deserves a place among the heroes of football even though he never earned a penny from playing the game.