By Vince Cooper

WE’VE all heard the expression that a specific footballer plays or played the game ‘with a smile on his face’. One player this seemed particularly true of was Alex Jackson. He was a Wembley Wizard, a scorer of the first-ever hat-trick on the famous ‘hallowed turf’, and a superstar

But four years after his Wembley heroics Jackson, who the Daily Mirror had called ‘The Player of the Century’ was gone from the English professional game at just 27 years of age. And it wasn’t injury or illness that forced him out of the game; it was money.

Alexander Skinner Jackson was born in 1905 and started playing football for Renton Victoria close to his home, 20 miles north of Glasgow. He would later say of his home; “It is just a small agricultural district where every boy and every girl play football all year round. That football madness may seem somewhat crude to the civilised south but there’s no doubt that it bred footballers”.

it was whilst playing for Victoria that Alex he was spotted by Dumbarton who made an offer for his services Renton couldn’t refuse – a football. In return for the ball Dumbarton got themselves an excellent player, a winger with pace and close control rarely seen. But after a single season Jackson was on the move again, and to an unlikely place.

In the summer of 1923 Alex and brother Wattie, who had been playing for Kilmarnock, went to visit another brother, John, in Detroit, Michigan. There they were contacted by representatives of Pennsylvania team Bethlehem Steel of the American Soccer League. Wattie was offered $25.00 per week to sign. It’s not known how much Alex got but in all likelihood it was considerably less as Wattie was the senior and more experienced Jackson and got all of the press coverage on signing. This was triple the money he was being paid in Scotland so the brothers decided to stay.

The brothers spent a season in the U.S. and Alex tried his hand at Baseball where he felt he could have made a living as a pitcher. He scored 14 goals in 28 games with no less than the New York Times complimenting him for having ‘the speed of a deer and dexterous footwork’. Wattie bagged 13 in 23 as Bethlehem finished 2nd in the league but in the summer of 1924 they returned to Scotland, signing for Aberdeen.

They had left for home supposedly ‘on a visit’ and had assured officials at Bethlehem that they would return in four weeks. In reality the pair had already agreed to join Aberdeen and four days after their boat docked both made their debuts for their new team causing much outrage in America. The United States Football Association complained to their Scottish counterparts but it fell on deaf ears.

That the Scottish FA took little notice of the Americans should come as no surprise given that the ASL had been prying players from them for a number of years by outbidding their Scottish League counterparts.

Alex spent a single season with Aberdeen and won his first Scottish cap while at the club after being described in the Scottish press as being ‘fast with good ball control and a sinuous swerve which is very perplexing’.

Huddersfield Town days

English clubs were all over the youngster with Liverpool, Everton, Aston Villa, Sunderland and Bolton Wanderers in the hunt for his services before Herbert Chapman’s Huddersfield Town splashed out £5,000 (Wattie would leave the following year for Preston before eventually returning to the U.S. to play for Bethlehem).

The deal was sealed when Chapman travelled to Renton to get his father’s blessing. He took Mr Jackson Sr to a local hostelry for a drink ‘and a lemonade for the boy’. He then generously offered to buy a round for the two or three other locals in the pub; ‘to drink to Alex’s success’. “That started it”, Alex would recall much later. “They came running from all around town. They even came from the hillsides to join in the hospitality. Even some of them who never touched a drop crowded in to get something for nothing.

“Chapman didn’t turn a hair although it must have cost him pounds out of his own pocket. I knew then I was dealing with a real man.”

Huddersfield were already English champions when Jackson signed but his trickery and pace took them to another level. Despite Chapman leaving for Arsenal a year later, the player thrived, and was described by one sports paper as being ‘born with a genius for the game’.

Jackson spent five years at Leeds Road, winning a title in his first season, finishing runner-up twice and appearing on the losing side in two F.A. Cup finals.

Although nominally an outside-right, Jackson was as happy cutting inside or, indeed, playing through the middle, a rarity in those times. Nicknamed ‘Jack-in-the-box Jackson’ by famous reporter of the time Ivan Sharpe, he increased the versatility of forward play and would often be found alongside the centre-forward when balls were being crossed from the opposite wing.

On international level he is surely best remembered for his performance in a more central role on one particularly memorable occasion.

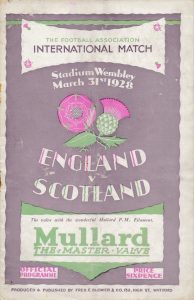

Having made his Scotland debut in 1925, the following year he got the only goal in his country’s win over England at Old Trafford, and two years later he travelled to Wembley as a key part of a diminutive but deadly front line.

Jackson is out of the picture but has just scored for the Wembley Wizards

The Scotland selectors had received a great deal of criticism for their team choice for Wembley. Established stars Jimmy McGrory and Davie Meiklejohn were left out. Eight Anglos (Scots playing in the English Football League) we’re picked.

At 5’9” Jackson was the tallest member of the forward line at Wembley. Hughie Gallacher (Newcastle), Jimmy Dunn (Hibernian), Alex James (Preston North End) and Alan Morton (Rangers) completed the attack. What they lacked in height, these five more than made up for in skill and toughness.

Early on, England hit the Scottish post. Undeterred, the visitors went straight up the other end where a Morton cross was met by Jackson to give Scotland the lead. Just before half time a one-two with Jackson left James in the clear and he doubled the advantage.

The third goal came when Morton found Jackson again and when the referee played an advantage after Gallacher was fouled, James claimed his second, and his country’s fourth.

The ‘Wembley Wizards’ match ball on display at the Scottish Football Musuem

The icing on the Scottish cake came when yet another Morton cross was tapped into an empty net by Jackson who claimed the match ball and completed the first-ever hat-trick at Wembley. A late consolation from Bob Kelly did little to hide the fact the English had been thrashed in their own backyard.

In all Jackson would go on to total eight goals in 17 games fo his country, an amount which might have been greater were it not for the Scots selectors eventually turning their back on Anglos after the Football League announced that clubs would only be forced to release their players if it was to play for England.

Jackson continued to receive glowing praise. One profile in the ‘Sports Post’ called him; “A thing of grace, of action, of fire, of … he’s just alive with every mortal picture which shows activity” before later going on to add; “He is like a kitten on his toes. His judgment of position play is immense. He makes up his mind in a moment and he acts almost as quickly as he thinks”.

The Roman Abramovich era hasn’t been the only time Chelsea were big spenders. After winning promotion back to the top flight in 1929-30 manager David Calderhead was given the green light, and the money, to add big-name stars to the Stamford Bridge line-up.

With Chelsea and Scotland teammate Hughie Gallacher

Calderhead went on a spending spree, splashing out around £25,000 to recruit a pair of Wembley Wizards in Gallacher (for £10,000) and Jackson (for £9,500) along with fellow Scot. Alec Cheyne.

Jackson said the move came about because he ‘wanted a change’ but also admitted that his business interests would be improved by a move to the capital. Sure enough he was soon the landlord of a pub, The Angel and Crown in St Martins Lane whilst also taking a share in the Queen’s Hotel in Leicester Square, and was writing a weekly syndicated column. He was also a greyhound owner and very active at the Wandsworth track which he would attend regularly (he also tried to get the management at the South London track to start a football team).

Five (Chelsea) men in a boat – Jackson far right.

The result of Chelsea’s new arrivals was entertaining football but no honours as the team became the epitome of mid-table inconsistency. They came close once, reaching the 1932 F.A Cup semi-final but there they suffered a 2-1 defeat at the hands of eventual winners Newcastle United.

Chelsea 1931-32

Leslie Knighton, the manager who replaced Calderwood at Stamford Bridge, coined the term ‘The Wandering Winger’ for the player, and it was not simply due to his play but also his antics off the pitch. The new manager later said; “Football gossip attached itself to him like barnacles to a ship. A genius – but with the temperament of a genius – rumours followed him everywhere”.

Still, he was loved at Chelsea by fans and initially by those in the boardroom (where he was the only player allowed), with one of the directors handing him the match ball on one occasion and telling him he was captain without the knowledge of the manager or his teammates.

But the situation changed quickly. On a trip to play Manchester City, Jackson ordered drinks for the entire team to be sent to his room on the night before the match. The directors, unhappy with this open show of rebellion, fined and suspended him, told him he would never play for the club again and put him on the transfer list.

Jackson felt he was being victimised and readily admitted that he had become unhappy at Stamford Bridge. Along with a number of other players he was approached by French club Nimes and offered a bumper deal to move across the channel. He was 27 and in his prime. He insisted that if Chelsea wanted to keep him they would need to break their maximum pay rule. The club refused and it turned into a stand-off between club and player and in such a situation at that time there could only be one winner.

Chelsea had the upper hand. They held the players’ registration and could simply refuse to pass it on to another English team which is exactly what they did. Cheyne went to France (though he would return two years later), Tommy Law and Hughie Gallacher priced themselves out of the move and ended up staying at Chelsea. As for Jackson, he didn’t move to France but also didn’t want to play for Chelsea anymore

The only way Jackson could carry on playing was to move into the non-league ranks and play for a team not covered by the registration ruling. He joined one such team, Cheshire County League side Ashton National. His new club paid him £15 per week as an employee (he was on £8 at Chelsea) but soon realised that the inflated salary was sending them hurtling towards bankruptcy.

Ashton National finished 6th in the Cheshire County League that season but Jackson, agreeing to sacrifice himself to ensure the club survived, was gone before the end of the campaign. His next stop was the Kent League where Margate paid him £10 per week. He made a mere seven appearances for the south coast club but helped them to win the title.

He was told at the end of the campaign that Chelsea would allow him back into the fold, if he accepted the error of his ways. “I made a special journey to meet Jackson during the summer”, recalled Knighton.

“And I came to the view that nothing could be done – nothing at all.

“Alas there are some tasks that are beyond mere enthusiasm”.

So the man also known as ‘The Gay Cavalier’ by some shunned the game but used his fame, taking on roles advertising cigarettes and a bookmaker. The Football League took a much more serious view of the second of these and he would have been banned – were he playing.

After this Jackson finally got his move to France. In the summer of 1933 he got married and took his wife to Paris for their honeymoon. With Chelsea still asking £4,000 for his registration he signed for OGC Nice who didn’t need the registration and he spent a season there before one with Le Touquet after which he hung up his boots. He was still only 28 years old, and in his prime, but the man who had been dubbed the best player in football a mere three years before was out of the game, and there he would stay.

It is clear that he was embittered with Football. As he said after leaving Chelsea: “After my experience in this country I would not be sorry to put a finish to my playing career”.

Little is known of what Jackson did in the years leading up to the 2nd World War, although it is thought that he still managed the pub. What is known is that once hostilities started he quickly signed up, joining the 8th Army and going to fight in Egypt. He turned out for the Army in a match against the R.A.F and, according to one soldier in attendance; “made us all rub our eyes with his uncanny control of the ball.

When the war ended he volunteered for extra service, working in the Suez Zone. In 1946 he was driving a truck in Libya when it overturned. Jackson was fatally injured. He left behind nine-year-old twins (called Alex and Grace) and grieving widow Grace and is buried in the Fayid war cemetery in Egypt..

The noted football writer John McAdam once said of Jackson: “There have been good footballers and dashing footballers and gay footballers, but never in my experience of the game have all these qualities become fused in the character of one man as they were in Jackson”.

It is quite astonishing to think that everything Alex Jackson achieved in football came before he reached what could well have been his prime. And tantalising to wonder what might have been if the winger had curbed the wandering just enough to carry on playing.